The Tunnel Beneath Us

Spring 2012

We heard the collective groan when PennDOT announced the Squirrel Hill Tunnel would be under construction for the next three years. Could the traffic bottleneck on the Parkway East really get any worse? Sure, it will be a hassle, but we saw the $50 million rehabilitation project as an opportunity to reflect on the history of one of our area’s most significant landmarks…

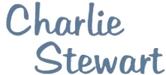

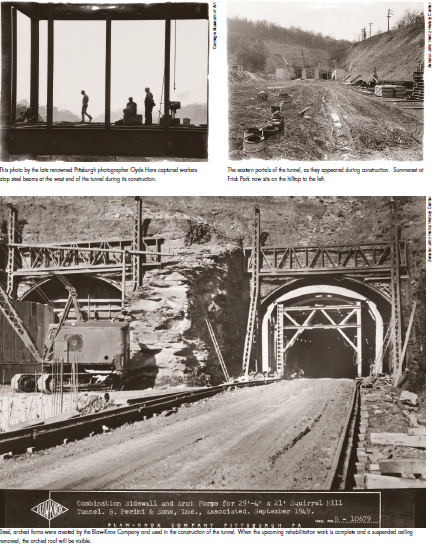

Ordinarily, kids aren’t allowed to play on the highway, but on the afternoon of June 5, 1953, the Taylor Allderdice High School band performed at the western portal of the Squirrel Hill Tunnel for the dedication of the Penn Lincoln Parkway East. The brand-new, eight-mile stretch of highway from hurchill to Bates Street in Oakland was the initial phase in the creation of a total of 27 iles that would carry Routes 22 and 30 to and through Pittsburgh and then westward until he approach to the Greater Pittsburgh Airport that

had opened the year before.

But getting there first required the monumental undertaking of digging through the high ground in Squirrel Hill. The result was the Squirrel Hill Tunnel, which has been a vital link in Pittsburgh’s development ever since. It was the second of the city’s three major tunnels to be completed and ranks as the 17th longest vehicular tunnel through a hill or mountain in the United States.

The Squirrel Hill Tunnel is so much a part of our lives, yet at times unseen, lying quietly 200 feet below us as we drive along Morrowfield Avenue or stand on the playing fields of Community Day School at the intersection of Beechwood Boulevard and Monitor Street. Its story dates back to the Model-T days of the 1920s, when a group of engineers first conceived of the idea for the road that would become the Parkway East.

Getting the Parkway East approved and built was a true test of perseverance, political will, and persuasion. From 1935 until the parkway’s completion, planning and implementation ultimately spanned the administrations of six governors, two boards of county commissioners, and three mayors. The project had the backing of the Allegheny Conference on Community Development and such key figures as Richard K. Mellon and state attorney general James H. Duff of Carnegie.

Through their influence, Governor Edward Martin announced a $57 million improvement program in 1945, which included the construction of Point State Park and the Penn Lincoln Parkway East. “This is the greatest combination of improvements ever before undertaken by the state for the benefit of the western part of the Commonwealth,” Martin declared at the time.

Before the Parkway, traffic from the eastern suburbs was congested going into Downtown via Routes 22 and 30, which overlapped starting in Wilkinsburg. From there, the convoluted route of the combined Route 22/30 traveled through the East End neighborhoods of Point Breeze, Squirrel Hill, and Oakland. Traffic flowed from Penn Avenue to Dallas; left on Dallas; right on Wilkins; left on Beeler; right on Forbes; and onto the Boulevard of the Allies to Downtown.

“It was slow-going,” remembers Shadyside resident Henry Hoffstot, who was 35 when the Penn Lincoln Parkway East opened. He used to drive Route 22/30 in his 1931 Pierce- Arrow sedan going to and from his wife’s farm in Ligonier. “I would take side roads just to avoid the traffic on Penn Avenue,” he recalls. While determining the final corridor for the Parkway, alternate routings—such as going through a central portion of Frick Park and tunneling under Schenley Park—were considered and dismissed. An open cut into Squirrel Hill that would have destroyed an entire residential neighborhood, including the Morrowfield Apartments, Taylor Allderdice High School, and the former St. Philomena’s Church was even contemplated.

In 1939, the Pittsburgh Regional Planning Commission retained Robert Moses, one of America’s foremost urban planners, to develop a long-term plan for reconfiguring the highways into and out of the city. In modified form, the design Moses referred to as the “Pitt Parkway” was adopted, according to Todd Wilson, a Squirrel Hill resident and traffic engineering consultant who has studied roads, bridges, and tunnels since boyhood.

“Robert Moses was the one who developed all of the parkways in New York City and all of the infrastructure improvements,” Wilson says. “Originally, the parkways in New York were built to link parks together. The automobile was a luxury in the 1920s and 1930s, and people would get in their cars and drive to the park and have picnics. It was a weekend outing. That’s how the term ‘parkway’ came to be.”

The Parkway East was aligned to weave through previously undeveloped or underdeveloped hillsides and creek valleys, so as to minimize the destruction of properties and developed areas, according to Wilson. “Following the tributaries of Nine Mile Run and Four Mile Run, the only major obstacle in this alignment was the high ground in Squirrel Hill,” he says.

Michael Baker, Jr., Inc.—on the way to becoming one of the country’s largest engineering design firms—was selected as the principal designer of the Parkway East, including the Squirrel Hill Tunnel. It was the first major highway design contract awarded to a private consultant by the Pennsylvania Department of Highways. With the retention of Norwegian-born Ole Singstad, a civil engineer and internationally recognized tunnel authority, the design task commenced.

Daily traffic was predicted to reach 40,000 vehicles a day by 1960. To handle this volume, twin bores roughly 29 feet wide and 4,225 feet in length (eight-tenths of a mile) were approved. Each bore would have two, 12-footwide lanes.

Louis Perini, president of B. Perini & Sons, Inc. of Massachusetts, won the bid to construct the Squirrel Hill Tunnel, which eventually came to $18.1 million—then the largest single contract ever granted by the Pennsylvania Department of Highways. Perini had not gone past eighth grade, but his firm was noted for doing high-quality work on challenging projects, such as the Tuscarora Tunnel on the Pennsylvania Turnpike.

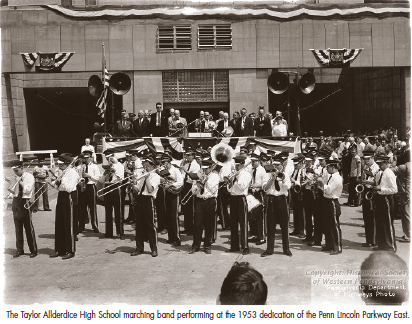

Pittsburgh Press reporters following the tunnel’s progress noted that “workmen began hacking into the hillside above Commercial Avenue near Frick Park on September 7, 1948.” Excavation started ten weeks later. The men drilled both tube faces simultaneously, using “30 pneumatic rock drills that pierced a total of 114 holes for each blast.” Twenty men to a crew, working three shifts a day, made their way through Squirrel Hill’s sandstone, limestone, and shale at a rate of 12 to 24 feet a day.

It was said to be like working in a coal mine, where the risks are high; the lives of three workmen were claimed, including Evert J. Hungerford and John E. Morse, who both died in a rock fall on February 14, 1948.

In all, 400,000 cubic yards of rock and earth (enough to fill the Rose Bowl in Pasadena) were excavated and loaded onto dump trucks. One ingenious contrivance was a large turntable that turned the trucks around inside the tunnel so they could conveniently exit with their loads.

When a section of the tunnel was cleared, a preassembled, reusable steel form, patented by the Blaw-Knox Company of Blawnox, would be rolled into the tunnel on rails. Concrete was then pressure-forced behind the form to seal all crevices and encase the rock and earth in solid barriers. Modified somewhat, the same forms were used for lining the walls of the Fort Pitt Tunnels with concrete.

The Parkway East opened with great fanfare in 1953, Allderdice marching band and all. The outlook of Pennsylvania’s Department of Highways, as written in a pamphlet distributed for the dedication, was optimistic and romantic:

“As motorists travel the Penn Lincoln Parkway East, they are impressed by a sensation of free and open space, both on the roadway and off to either side in sharp contrast to the jam-packed traffic encountered on entering streets. The sensation is akin to flying at low altitudes as they skim along above buildings and the Monongahela River.”

Angry motorists today inching toward the Squirrel Hill Tunnel entrance at rush hour might beg to differ. Is there some sort of spell that takes hold of drivers and makes them slow down when approaching the tunnel? Fanciful theories abound. It’s claustrophobic. There’s a monster in there. It’s a Pittsburgh custom to brake for tunnels.

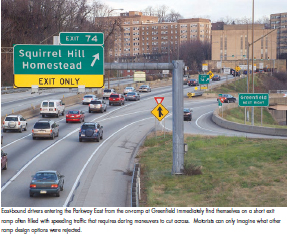

Engineers point to two main causes of congestion. First, the tunnel was designed to handle 40,000 vehicles a day, but traffic volume has increased by 10,000 every decade, so 105,000 vehicles now try to funnel through each day on average. And as anyone who has risked life and limb entering the Parkway at Greenfield toward Monroeville could tell you, the on-ramps create slowdowns as vehicles merge.

“We have about 30 incidents per week at the Squirrel Hill Tunnel,” says Tom Diddle, PennDOT highway maintenance manager and supervisor of the crew of 15 who work in shifts 24/7 to respond to emergencies and monitor and maintain the tunnel. Incidents include not only overheight trucks getting stuck (which happens just once or twice a year), but also trucks that must turn around because they missed the last exit after triggering the overheight sensors. Add to all this flat tires, breakdowns, people running out of gas, and accidents, and you have a serious bottleneck.

“Sometimes you wonder how people can be in an accident when they are only going five miles an hour,” laughs KDKA/AAA traffic reporter Kathy Berggren, who observes traffic slowing to a crawl by 6 a.m. at the tunnel on weekdays.

“The Parkway East ranks 26th in the nation, when measuring per-person-hours delay per mile during the morning rush hours,” says Bill Eisele, a research engineer at the Texas Transportation Institute (TTI) and co-author of the 2011 Congested Corridors Report, the first nationwide effort to identify highway stretches that cause significant congestion. Over an entire year for the Parkway East, TTI estimates 1.3 million person-hours of delay, 724,000 gallons of wasted fuel, and a total cost in time and fuel of $31 million.

Don’t expect the situation to improve when PennDOT finishes the $50 to $60 million makeover of the Squirrel Hill Tunnel that is scheduled to get under way this spring. It is approaching 30 years since the last rehabilitation of the tunnel in 1983, according to PennDOT District 11 executive Dan Cessna.

“The major change in appearance that motorists will notice is that the arched tunnel roof is going to be visible when the existing six-inch, cast-in-place suspended ceiling is removed,” Cessna says.

The ceiling height is currently 13’ 6”. It will be posted for 14’ 9” eastbound and 15’ 6” westbound after the work is completed in July 2014. “Trucks have gotten taller,” he explains. “And this will reduce the number of overheight trucks being stopped.”

Still, the renovation is not going to relieve congestion on the Parkway East. “That is not the intent of the project,” Cessna says. “The intent is to ensure the structural and physical capacity of the tunnel for the next 30 years.”

Meantime, the traffic will certainly get worse, as you can look forward to the usual single lane restrictions—from 10 p.m. to 5 a.m.—and tunnel closings (eight full weekends for each of the two tunnels) over the next two years.

So take a deep breath, recline your driver’s seat, and tune in your car radio to Kathy Berggren reporting, “The Parkway East is backing up to Wilkinsburg from the Squirrel Hill Tunnel.”

With many thanks to SHADY AVE magazine for granting me permission to reprint on my website.