East Liberty On Target for the Future

Fall 2011

A few big things happened in East Liberty over the summer, and they’re bringing attention and people into this neighborhood that’s undergoing a resurgence.

The ringing of the bell at Target’s Minneapolis headquarters at 9:30 a.m. June 9 marked the culmination of a seven-year process by The Mosites Company to woo the store to East Liberty. The attorneys had dotted every i, the lease was signed, and the financing closed. Company president Steve Mosites and Mark Minnerly, director of real estate development, along with the entire office staff, were on speakerphone. “That was the moment of truth—and it was a blast,” Minnerly recalls.

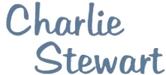

Target is opening 21 stores nationwide this year, but the sound of the bell chiming for this location

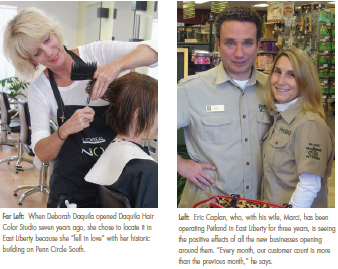

heralded more than just the arrival of another big-box behemoth. East Liberty is making an extraordinary comeback, with stores, businesses, hoteliers, restaurants, and people moving in to revitalize the once-blighted neighborhood. And the red Target bull’s eye overlooking the corner of Penn Circle South and East is a symbol of this newfound stability—and hope.

It’s the kind of hope that has persisted here since the vibrant heart of East Liberty was cut off by a failed urban renewal program in the 1960s, followed by years of neglect and decay. The program eliminated about a million square feet of commercial space to make the East Liberty commercial core—once Pennsylvania’s third-largest shopping district behind Philadelphia and Downtown Pittsburgh—into an urban-style strip mall, explains Skip Schwab, director of operations at East Liberty Development Inc. (ELDI), a nonprofit community development group.

“It resulted in a state-maintained, one-way road being built around the neighborhood,” says Schwab, referring to Penn Circle. “You were supposed to park in one of the new, numerous surface parking lots inside the ring and then you would walk and do your shopping in the district. The problem was that no one came into the district because they couldn’t understand the traffic pattern. It was more convenient to drive around and away from the district than it was to drive and park and go into East Liberty.”

Reversing that one-way traffic flow has been a key to East Liberty’s rebirth. The city’s Department of Public Works completed the $5 million two-way conversion in May, and Minnerly drove his BMW convertible in a “parade” of one car as the first to go west on Penn Circle South. Bill Kolano of Fox Chapel, president of Kolano Designs in East Liberty, rode beside Mosites on the back of the car and says he “waved to no one” at that early hour.

“When we finally drove it, it felt like we were doing something very wrong,” Kolano laughs. Kolano’s office is in the row of historic buildings along Penn Circle South. “We came here in 1988 as urban pioneers, so we have been waiting for the conversion since then,” he says. “The ring road has been a huge barrier, and now that the moat is gone, we are going to see more development toward East Liberty’s core.”

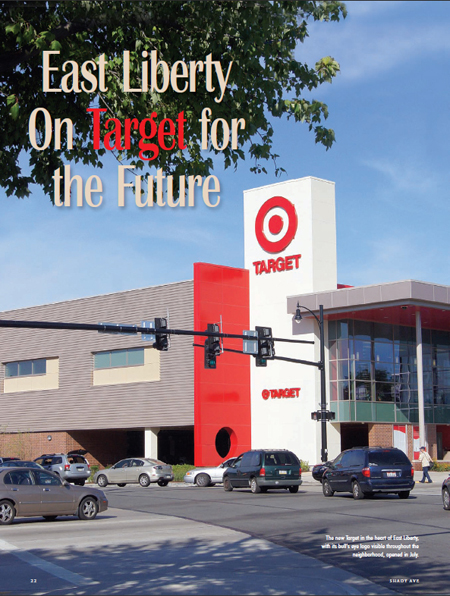

The benefits to the community are already being felt in the form of new work opportunities. So far, Minnerly estimates, his company’s projects—they include the nearby Whole Foods Market and phases I and II of the EastSide developments (everything between Whole Foods and Highland Avenue), as well as the new Target—have generated 600 jobs. Target alone is expected to create 250 jobs, not to mention generating $1.62 million in state and local tax revenue.

The neighborhood has also benefited from streetscape improvements, such as sidewalk repairs and new benches and trees. And more people will be able to walk or bike to work and shop when the $1.5 million pedestrian bridge spanning the busway to connect Shadyside’s Ellsworth Avenue with the upper level of EastSide is completed this winter (see page 28).

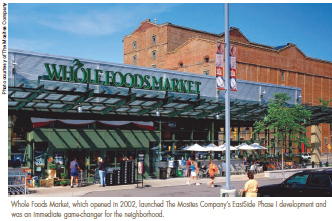

With the EastSide development, it has been all about making connections—connecting Shadyside to East Liberty, “blurring the lines” as Mosites thinks of it. The connections will continue as the company pursues EastSide phases III and IV by developing a transit center. Some 33,000 passengers pass through the bus station here daily, making East Liberty the busiest Port Authority hub after Downtown. Current plans call for a retail and office complex facing Target, with a potential hotel on Highland Avenue and connector parking in between.

“We are calling this the eastern gateway to East Liberty,” Minnerly says. “It’s the clincher that is really going to glue this whole thing together.”

The progress to date has enabled other developers like Walnut Capital president Gregg Perelman to take their own risks. “Steve Mosites was a true trailblazer when he brought Whole Foods here,” Perelman says. “That was a major coup, and from that everything got started. I don’t think Bakery Square would have even been on the radar screen if he hadn’t done what he did.”

Bakery Square in neighboring Larimer is a $130-million development in the former Nabisco plant on Penn Avenue that was completed last year and benefits from its proximity to the universities and hospitals in Oakland. Google’s recent expansion and the trendy retailers and sleek hotel that chose to locate there lend a cool glow to the whole area. “We love the atmosphere,” says Jennifer Palashoff, co-owner of Learning Express toy store. “There’s an urban feel, and it’s a cozy, comfortable place to be.”

Seeing new opportunity closer to East Liberty’s core, Shadyside-based Walnut Capital is partnering with Massaro Properties to renovate the 102-year-old, 13-story Highland Building designed by Daniel Burnham for Henry Clay Frick. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the long-vacant building would be purchased from the Urban Redevelopment Authority using historic tax credits and federal funding. The roughly $23-million project incorporates the adjacent Wallace Building to make 120-plus one-bedroom, market-rate apartments.

A three-tier parking garage accommodating 175 vehicles will be constructed between the two structures once all financing is secured—the essential element that has stymied other potential developers. The Urban Redevelopment Authority has performed the demolition work to ready the site in anticipation of the project moving forward. “We are supposed to receive a $4.5 million Redevelopment Assistance Capital Program grant from the governor,” Perelman says. “The garage and the apartments are tied together, but if the garage money doesn’t come in, we don’t build the project.”

New residential space will add to the increasingly high quality of urban living now found in East Liberty, thanks in part to the neighborhood’s growing and diverse restaurant scene. Just around the intersection of South Highland Avenue and Penn Circle South alone, you can find authentic French fare; pan-Asian, Caribbean, and Ethiopian food; modern American cuisine, gourmet burgers, designer cupcakes, and upscale pizza.

“All the different restaurants in the neighborhood are bringing people from all over,” says Susanne Gaetano, who’s been operating her women’s clothing boutique, Panache, on Penn Circle South for 28 years and only now finds the need to stay open later than six o’clock. “I stay here sometimes until nine or ten o’clock at night,” she says. “It’s just amazing that we’re getting that many people walking around in the evening. You feel like you’re in the middle of Manhattan.”

The nightlife continues at the Kelly- Strayhorn Theater, a community performing arts center in its 11th season, and the nearby Shadow Lounge and AVA performance spaces.

Now that more people are spending time shopping and dining in the neighborhood, it only follows that an increasing number are considering living there.

“It’s a good place to live,” ELDI project manager Kendall Pelling says. “We have a lot of prospective home buyers now in East Liberty,” he says. “People who never thought they would be buying here a good number of years ago are now buying at prices that nobody would have thought we’d be getting here.”

ELDI controls about 15 percent of the approximately 1,200 residential parcels in East Liberty, including abandoned, vacant, foreclosed, liened, and other “nuisance” properties, which the organization can then make available to new buyers. “Having stabilized all the subsidized rentals that were in the neighborhood, we are now able to have the older historic parts of the neighborhood become more stable,” Pelling says.

The proof is in median home prices in the 11th Ward, including East Liberty and Highland Park, which grew a staggering 38 percent from 2007 to 2010 despite the nationwide collapse in the housing markets, according to Pelling. He is excited by these results. “We are able to build homes now without major amounts of subsidy in them,” he says. “It means that the private market is working. It means that you can buy a house in East Liberty that needs a lot of work, do all the work that you want to do to it, and still be able to sell it for a price that’s appropriate.”

The long-term goal is to transform East Liberty into a sustainable, mixed-income community. “I guess you could say we are halfway there,” Schwab says. “The other half is the continuation of our work both in the residential enclave in East Liberty, as well as the balance of the commercial core.”

Success to date has come from following the advice of a national development firm called Streetworks. “They told us very clearly that our strategy should be to build on the strong edges of the community, which is that zippering area between East Liberty and Shadyside, now the Whole Foods/EastSide development,” Schwab says. “And that the last thing we would be doing is working in the historic core.”

A first step toward that end was to apply for designation as a national historic district, which East Liberty was awarded earlier this year. Now ELDI is working to adopt a centuries- old concept—the town square—in the historic center of the neighborhood. “The idea is to think of the area around East Liberty Presbyterian Church as being like that of a European cathedral with a lot of street activity and retail encircling it,” Schwab says.

Paul Brecht, a Point Breeze resident and executive director of the East Liberty Quarter Chamber of Commerce, envisions keeping the legitimate stores along Penn Avenue in the core of the retail district. “They are good business people,” Brecht says. “They’ve kept that block alive and they deserve to be there. But if you brought in other quality stores, that can only help them.”

“These are exciting times,” he continues. “Just 15 years ago we had gang warfare. It was hard to envision all of these developments happening because things were so tough at the time. Now we have to make it very, very attractive.”

One person doing his part is Matthew Ciccone, who teamed with Nate Cunningham of ELDI to convert a former hair salon along Penn Avenue into a shared space called The Beauty Shoppe, where freelancers and start-ups can rent a small office or conference room on a monthly basis.

“What’s interesting to me is that you look down Penn Avenue and also Highland, and you see a lot of facades that look empty, but are not necessarily,” Ciccone says. “There’s some really innovative start-up energy happening here on this street.”

The per-person user fee at The Beauty Shoppe totals the approximate cost of three cups of Starbucks cappuccino. “When we first started, we talked to people who said, ‘If it’s more expensive than Starbucks, we are going to work at Starbucks,” Ciccone recalls. “And so we sat down and said, ‘OK, great, what does that mean? Three cappuccinos a day, $3 per cappuccino is $9 per day. Twenty working days a month comes to about $175 dollars.’ That’s our price.”

But if you are still missing that cup of coffee, you can go downstairs and meet Chris Rhodes, who just opened Zeke’s Coffee, a small batch roastery at 6012 Penn Avenue, which he rents from ELDI. “I’ve lived here in East Liberty since 2006,” Rhodes says. “It seems like every person I meet is a good person, so I’ve kind of fallen in love with it.”

So has Cathy Mallery, a resident of Mt. Lebanon who last year opened an Edible Arrangements franchise at the Village of Eastside on Penn Avenue, providing fresh cut fruit made to look like flower rrangements. “I’m told this used to be a jewel part of the city,” Mallery says. “And whatever it was that happened years ago, I feel they will reclaim that back and I want to be a part of it.”

Michael Samakow witnessed firsthand what happened years ago. He was fifteen in 1969, when the city’s first urban redevelopment initiative for East Liberty forced his family’s business, Masterwork Paint Company, to move from one side of Broad Street—where his grandfather had operated it for 30 years— to the other. Forty years later, once again for the sake of progress and redevelopment, the company moved its headquarters—this time to give Target the land it needed. But Masterwork remains in East Liberty.

“We made the decision to move for the betterment of the community,” says Samakow, now president of the company. “But we moved just over to Centre Avenue because we still wanted to be a vibrant part of the community. We saw what East Liberty was before its decline, and now we’re seeing its rebirth. It’s a nice thing.”

One major piece of the neighborhood’s renaissance has been the $6.1 million overhaul of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh’s East Liberty location. Anne Chen, a Friendship resident and principal at Garfield-based architectural firm EDGE studio, designed the renovation with her husband and business partner, Gary Carlough.

“We have been really thrilled by what’s happening here,” says Chen, who enjoys taking her young son on regular outings to the library. “Before, the library was really hidden, the door was on the side; and so we made it more recognizable. The library now says, ‘Look, we are here.’”

It must be working. “We do get a lot of foot traffic that we otherwise might not have had because of the architecture being so striking,” says Chris Gmiter, the library’s department head. “Our circulation is higher than ever, and we have seen a spike in people coming in to use any of our 26 computers to apply online for jobs at Target.”

Still, not everyone can find a job or food or shelter. That’s where the work of nonprofits in the neighborhood like Big Brothers Big Sisters of Greater Pittsburgh and the East End Cooperative Ministry (EECM) comes in. “As our neighborhood does develop, you have to make sure nobody falls through the cracks,” says Nathan Wildfire, ELDI’s director of planning and a Highland Park resident. “EECM is one of our partners in making sure that everyone is accounted for.”

For 40 years, EECM has made it a mission to account for the homeless, the hungry, the homebound, the mentally ill, recovering addicts, and others in need. The organization’s goal is to consolidate its operations, now spread across 14 locations, into one new facility to be called Community House, planned for the vacant site across from the Social Security Administration building, where Penn Circle East turns north. Fundraising is under way for the $15 million project.

“When I look around, I see wonderful new housing, but it is an attempt for everyone to live in the community at all socio-economic levels,” says EECM executive director Myrna Zelenitz, a Shadyside resident. “So that has increased our load of clients, because while people go back into housing, they really need our help to make sure that they are stable.”

“EECM is a vital part of the economic infrastructure of this revitalized community,” she continues. “And with a new building, there will be so many new opportunities available to us, including offering job training for the new economy here.” Some people are still wondering if East Liberty is really safe now.

“I used to tell people where I worked, and they would ask, ‘Isn’t that a dangerous place?’” says Chris Labishak, co-owner of Club One Fitness on Penn Avenue. “But I’ve always felt safe. It may still take a while for people to get over East Liberty’s reputation, but now Target should give people a sense of being safe because it’s familiar.”

Timothy O’Connor, a 29-year veteran of the Pittsburgh Police and Zone 5 commander says three bicycle officers are assigned permanently to the business district of East Liberty and EastSide. “They can cover a lot of ground, and we are working in conjunction with Target security,” O’Connor says. “I believe that as far as the business section of East Liberty, a person’s attitude could be comparable to going to Shadyside.”

Mayor Luke Ravenstahl is hopeful the successes achieved so far in the neighborhood can be leveraged to go beyond East Liberty to Larimer, Garfield, and Homewood. “By aggressively marketing neighborhood properties for new redevelopment opportunities, we are making sure that Pittsburgh’s Third Renaissance expands beyond Downtown’s borders,” Ravenstahl says. “As we work to transform places like East Liberty into economic engines, we will see more prosperity and growth happen in surrounding communities.”

Completing the road conversion around the rest of Penn Circle will be a logical next step in making more of those connections. “There is a master plan,” says Pat Hassett, the city’s assistant director of public works. “But there is nothing in the books yet for converting Penn Circle North and West to two-way in the immediate future.”

That’s all right with Sue Anderson, owner of Meadeworth Interiors, which sells high-end furniture, lighting, decorative accessories, and design services on Penn Circle West at the opposite end from Target. She remembers opening in 1995 when just a car wash and a Yellow Cab headquarters existed near where Whole Foods is today.

“Everything is really moving in a very positive direction,” Anderson says. “But at the pace the two-way conversion is going, my corner— if you can have a corner on a circle—will be the last to get done. But you know what? I like to think of myself as being the anchor on this end of it, because we started it over here on this corner, we have stuck with it all these years, and we’ll be here when the two-way conversion gets here.”

In his 1901 memoir, Pittsburgh publisher and author William G. Johnston* described the neighborhood of East Liberty as it appeared in the 1840s: “The road bending to the south, soon another scene of tranquil beauty was spread at our feet, one which I doubt has its equal this side of heaven—the charming valley of East Liberty.”

Once a haven from industrialization, that charming valley became a thriving retail center, only later to fall victim to a disastrous attempt at urban renewal. East Liberty will never be the pastoral setting of yesteryear, but it is being restored to a beauty of its own—a diverse, interdependent community designed by the stakeholders who care the most.

With many thanks to SHADY AVE magazine for granting me permission to reprint on my website.