Manor Magic

Summer 2012

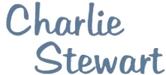

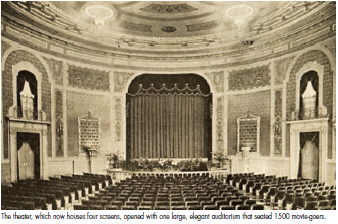

When James B. Clark of Rowland & Clark Theatres opened the Manor Theatre in Squirrel Hill on May 15, 1922, its auditorium accommodated 1,500 moviegoers—making it one of the most spacious in all of Pittsburgh.

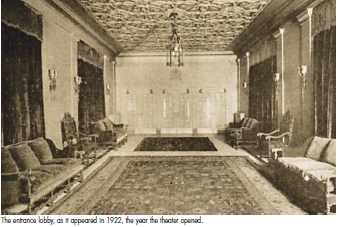

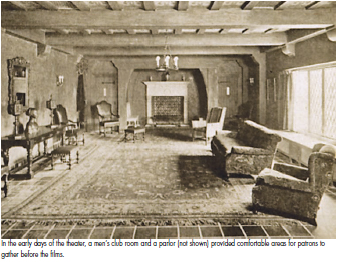

“Squirrel Hill’s Manor Has the Atmosphere of a Country Club” read a headline of Moving Picture World magazine that summer. The Murray Avenue building, designed by H.S. Blair as a blend of Elizabethan and Tudor styles, was intended to “harmonize with the surrounding handsome residences.” A fireplace accented the parlor, the men’s lounge was finished in dark oak, and the foyer floor was made of marble. Heavy velour draperies, set in full-height panels, embellished the auditorium’s walls. It was grand.

As a neighborhood theater, residents could easily walk there. Typically, an evening’s entertainment included a feature, a comedy, and a short. On Saturday, August 23, 1924, for example, Never Say Die was the attraction, followed by Tootsie Wootsie and an Aesop fable.The projectionist would change over reels between two Simplex projectors running 35- millimeter film, the standard format that has been used at the theater ever since it opened.

Until now.

This summer, the Manor Theatre—the oldest operating movie house in Pittsburgh and one of the longest continuously running businesses in Squirrel Hill—is celebrating its 90th birthday with a conversion from 35mm film to digital projection.

“It’s like comparing old-fashioned television to flat-screen, high-definition home theater,” says longtime owner Rick Stern, 58, a Fox Chapel resident who grew up in Squirrel Hill. “The crisp, clear sound qualityis amazing. No more flickering from film being fed over sprockets.”

Two-thirds of all indoor screens in the country have converted to digital, according to Patrick Corcoran, director of media and research at the National Association of Theatre Owners. “The transition to digital cinema represents the most significant technological change in the theater industry since the advent of sound,” Corcoran says.

Stern is taking advantage of a 10-year financing deal whereby the film studios— which save money by shipping digital files instead of 35mm prints—will pay the theater a “virtual print fee” each time a first-run movie is played. He will recoup most of the $300,000 investment required to install an upgraded sound system, server, and four Sony 4K digital projectors—one for each of the theater’s four screens.

“We estimate the film studios collectively will save a billion dollars per year once they stop shipping film prints, which will be sometime in 2013,” Corcoran predicts.

So it’s now or never for theaters to apply for the funding program.

“When you are looking at spending all this money for the digital conversion, you are making a real commitment to stay in the business for at least 10 more years,” Stern says. “And then the question you ask is, how far do you carry it?”

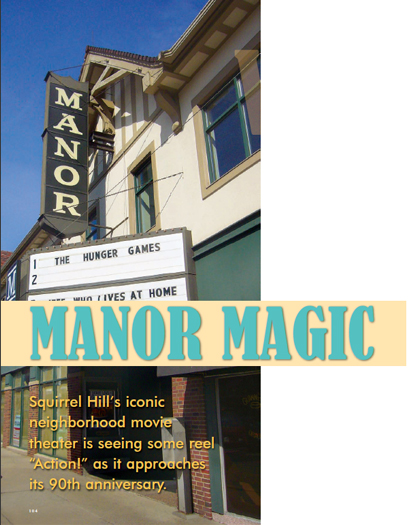

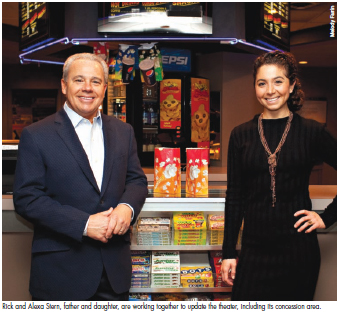

Stern’s daughter, Alexa, a Highland Park resident, helped make that decision. She worked as co-developer with her father to oversee what has become a $250,000 renovation, including the transformation of the concession area to a comfortable lounge and bar for patrons to enjoy an appetizer or cocktail.

According to a 2010 Nielsen survey, 42 percent of moviegoers dine out before or after the show. “We are hoping to capitalize on the dinner-and-a-movie date night experience,” says Alexa Stern, a psychotherapist at Mercy Behavioral Health.

Rick Stern is a seasoned restaurateur who owns Willow in the North Hills and Spoon and BRGR in East Liberty. He is drawing on these successes, while conferring with Brian Pekarcik, his partner and executive chef at the East End restaurants, on options for light fare that can be carried on trays that conveniently attach to the cup-holders. The offerings may vary—from Buffalo wings, kosher hot dogs, and personal pizzas, to panko crusted shrimp tempura, pot stickers, hummus and pita chips, and zucchini fries.

“Just fun stuff,” the elder Stern says. “We are even thinking of offering Coppola wines, which we thought would be appropriate since Francis Ford Coppola is a famous movie director.

Award-winning architect Jen Bee of Jen Bee Design designed the theater’s new interior. “We’ve brought out some of the original charm of the Manor,” says Bee, noting how a beautiful plaster medallion detail was uncovered when the original ceiling was exposed during the renovation.

Moviegoers will also enjoy the $100,000 investment in blue leatherette seating made by Greystone Seating, a Michigan-based Ford Motor Company spin-off. “The Manhattan rocker is the same seat as in a Lincoln Town Car,” Rick Stern says. These ergonomic, 40-inch high-backs are four inches taller than the previous seats, which were installed during a 2004 renovation.

Both Stern and his daughter laugh about growing up in the theater business. Rick Stern describes his grandfather, Norbert Stern, as a real estate owner and drive-in pioneer who opened South Park Drive-In in Bethel Park around 1939. It was the first in Pittsburgh and one of the first in the country.

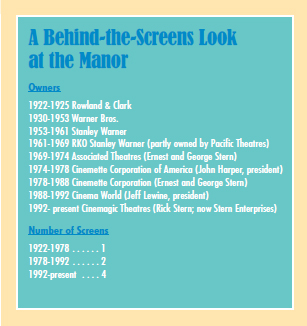

The next generation, Stern’s father, Ernest, and Ernest’s cousin, George Stern, bought theaters from owners who believed television would be the death of the film business. They built up their theater circuit, including the Manor, to 90 screens under the name Associated Theatres, which the Sterns sold in 1974 and bought back in 1978. By this time, the chain had grown to 200 screens in the tri-state area, representing most of the screens in Pittsburgh. The Manor then continued its convoluted ownership history, passing out of and then back into the Stern family in 1992.

“This is what I heard about every night at the dinner table,” remembers Rick Stern, whose first job was working the oncession stands at The Fulton (now the Byham Theater) downtown as a 15-year-old.

“My father, Ernest, was always buying or building theaters, so we were constantly going to theater openings,” he recalls. “And my Mom decorated a lot of the theaters. I remember them going to England and buying a suit of armor to display in the lobby of the King’s Court Theater [in Oakland]. It was an exciting business to grow up in.”

With the curtain closing on his Squirrel Hill Theatre in 2010, the Manor remains one of the last of the independent theaters in the area, along with the Regent Square Theater on South Braddock Avenue and The Oaks Theater in Oakmont.

“It was a tough choice to close that theater,” Stern admits. “We found that when we had the Squirrel Hill Theatre and the Manor, we were forced to play more commercial product and compete with the big boys down the street. There wasn’t enough specialized product to fill 10 screens.”

It’s a nationwide phenomenon. With the surge in multi- and mega-plexes, the number of indoor screens in the U.S. has increased over the last decade by nearly 10 percent to 39,042, while the number of indoor theaters

has declined by more than 20 percent to 5,240—about half of which have four screens or fewer like the Manor.

Upon closing the Squirrel Hill Theatre, Stern says what he heard from his loyal clientele was: “Please don’t close the Manor. Please make sure we always have our neighborhood theater.”

“So we said, ‘You know what, we know that the Manor is a special place, a gem of the neighborhood,’” he says. “We only have four screens now, so we no longer have to spread the product out anymore. We can pick and

choose all the best product that will do well in our specialized film market niche—limited release, art, foreign, upscale films that might play along with one or two other theaters in the Pittsburgh market.”

Movie-lovers from Squirrel Hill and well beyond have responded accordingly.

“The Manor is my favorite theater,” says neighborhood resident and pianist Yeeha Chiu, who likes to walk to see a film in good weather. “They have all the first-run movies I want to see. It’s a gathering place for Squirrel Hill.”

Rick Stern says that is very typical of comments he hears, which echo his own feelings for the theater. “The Manor holds a sentimental place in my heart—like a connection to my past and my childhood that I can’t give it up,” he says.

“I feel the same way,” Alexa Stern says. “It was my first job at 15 when I worked at the concession stand. It’s the last and only theater that my family owns, and I feel strongly tied to it.”

She continues: “When I think about trends in the movie business and other businesses, it’s always been ‘bigger and better.’ But I think there are a lot of people who reject that and want to keep businesses smaller and keep

businesses with history and character alive, and I think that we offer something different.”

“Here’s looking at you, kid.”

With many thanks to SHADY AVE magazine for granting me permission to reprint on my website.