The Place for Smiles

Holiday 2011

Schenley Plaza is entering the holiday season with a sparkling new restaurant, The Porch, adding an exciting new element to the popular Oakland green space. This striking, full-service eatery is the latest venture by Eat’n Park Hospitality Group, the company that operates the Eat’n Park restaurants that are so much a part of our community. With East Enders at its helm and corporate headquarters at the Waterfront, this Pittsburgh institution is building on a solid history and reputation as…

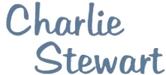

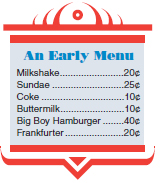

Come as you are—eat in your car. That was Eat’n Park’s very first slogan. It said it all. And come they did. In droves.

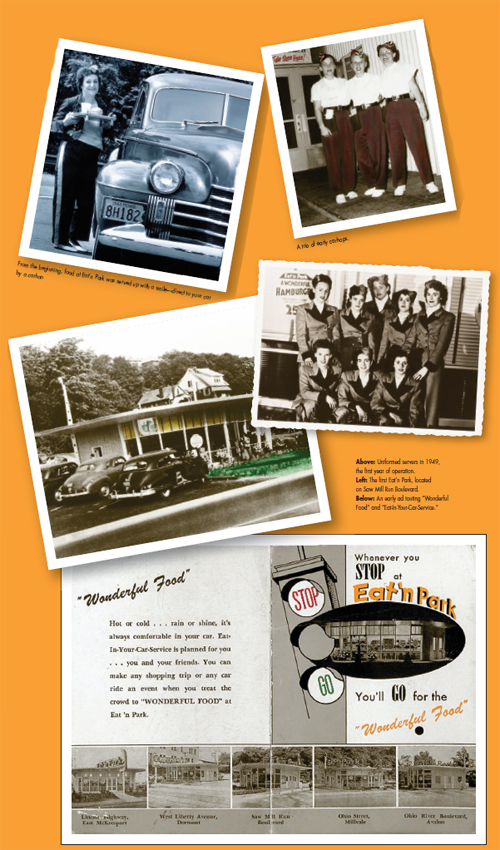

At 2 p.m. on Sunday, June 5, 1949, Larry Hatch opened the Pittsburgh area’s first drive-in. The tiny South Hills restaurant had just 13 seats inside. That’s because the action was happening outside, where 10 bustling carhops served guests in their cars.

With the opening-day menu featuring a double-decker hamburger for 40 cents and free ice cream sundaes, the restaurant was so popular that it caused an enormous traffic jam. Six ours after opening, Hatch and his staff

had to close to regroup, as they just couldn’t handle the business.

The drive-in was an instant smash hit. After all, the United States was in the midst of a post-war car craze, and folks were on the road to see and be seen in their snazzy convertibles, coupes, sedans, woodies, and roadsters.

About a year earlier, Hatch, then the general manager of Pittsburgh’s Isaly’s restaurant chain, had learned about Frisch’s Big Boy restaurant with car service in Cincinnati. He went to Ohio to see it for himself and immediately recognized the potential. A flier announcing Eat’n Park’s opening day on June 5, 1949, promoted a free ice cream sundae with any purchase.

Hatch presented Henr y Isaly with the idea, but according to Brian Butko’s history of Isaly’s, the restaurant owner declined. “I don’t want any part of them,” Isaly said. “You’ll go broke before the first winter.”

So Hatch went out on his own as a Big Boy licensee under the name Eat’n Park. By 1951, there were five Eat’n Parks in Pittsburgh, with managers largely recruited from Isaly’s. Indeed, the restaurant inherited the best elements of Isaly’s—good value and fun in a neighborhood setting, where smiles were common. After all, Isaly’s brought us Klondikes, chipped chopped ham, and the rainbow skyscraper ice cream cone.

But why not Park’n Eat? Logically, a customer parks first, then eats. However, in the late 1940s, “park & eat” was as common a sight as “drive-thru” is today and couldn’t be copyrighted. Hatch cleverly decided to reverse it to Eat’n Park, got it trademarked, and the catchy name stuck.

The first McDonald’s opened in Pittsburgh in 1957, and Hatch’s son-in-law, Bob Moore, had no doubt that “walk-ups” would spell the end of carhops. The service was faster because they cooked ahead of time—plus they had a cheaper menu, lower payroll, and customers didn’t have to tip.

By the late 1960s, Eat’n Park, with 25 restaurants, had to decide whether to remain in the carhop business, compete in fast food, or eliminate car service and use the excess parking lot space to convert to larger restaurants and coffee shops. They took the latter route. The company upgraded many of those coffee shops in the early 1970s, while also seeking new sites to build the family-style restaurants for which they are known today.

In 1973, Jim Broadhurst, who thought he would always be a banker, was persuaded by Hatch to leave his post as a commercial lending officer at Pittsburgh National Bank, where one of his accounts was Eat’n Park. He was named executive vice president and treasurer of the chain of 33 restaurants, many of which still had carhops. Appointed president two years later, Broadhurst would oversee the discontinuation of the last car service on December 26, 1977.

As a Big Boy licensee until 1976, Eat’n Park enjoyed an arrangement of paying one dollar a year for use of the “Big Boy” name. But after Marriott bought Bob’s Big Boy, it expected up to two percent of the revenue from each Big Boy hamburger sold.

“Since we were known in Pittsburgh as Eat’n Park and had very few Big Boy signs, all we needed to do was change the name of the sandwich,” Broadhurst remembers. Thus the “Superburger” was born and remains a favorite today, earning the title of “Best Traditional Burger” at the 2010 National Hamburger Festival.

On September 20, 1976, the Squirrel Hill Eat’n Park opened at its current location on Murray Avenue (formerly home to Modern Curtain & Rug, which moved down the street and later became Weisshouse in Shadyside.) Broadhurst recalls it being the first new restaurant in the area to feature live plants as part of the décor. He called Carole Horowitz of Squirrel Hill, who had just launched the landscape company Plantscape. Observing that the front window had maxi mum sun exposure, she proposed a cactus garden.

“Jim was such an innovator, as there were no live plants in restaurants at the time,” says Horowitz, whose business still installs and maintains Eat’n Park’s plants, including those at the corporate headquarters, which has been located at The Waterfront in Homestead since 2000.

Beginning in the 1970s, Eat’n Park restaurants installed six-seater booths, which were unusual in the industry, but designed so the whole family could sit together and enjoy each other’s company. Broadhurst had been president for five years when, in 1980, he approached Fred Rogers and his staff at Family Communications for advice on further enhancing the family experience by improving the children’s menu.

“Families were so critically important to Fred, and his mission was similar to ours in trying to improve children’s interactions with their families,” Broadhurst says.

The two companies began to collaborate on facilitating communication within the family and making kids feel special while having fun. As general manager of Family Communications, Squirrel Hill resident Basil Cox was assigned to lead the project, which involved creating placemats to color, as well as award-winning children’s menus in the form of flip books and those that folded into threedimensional shapes.

As a result of the successful relationship, Cox was hired as director of marketing for Eat’n Park in 1984. That same year, Broadhurst approached Hatch (who was nearing retirement), proposing that, should the business ever be for sale, he would like to be considered as a buyer. “The deal was made at that time, right there, that morning— the price and everything,” says Broadhurst, still amazed.

Broadhurst became chairman and CEO and promoted Moore to president. As the chain grew to 80 restaurants, including expansions into Ohio and West Virginia, perhaps the most astounding phenomenon was the rollout of the Smiley cookie.

As Broadhurst, who has lived in Squirrel Hill for 18 years, tells the story, he grew up in Titusville, Pennsylvania, and would stop at Warner’s bakery on his way home from Main Street Elementary School to buy a round sugar cookie with a painted smiley face for a nickel.“I bought so many cookies, my friends started calling me ‘Cookie,’” he recalls.

In 1985, with the idea of having Eat’n Park make the very same sugar cookie, Broadhurst enlisted the help of Warner’s bakery and Eat’n Park product developer John Vichie to duplicate the recipe for high-quantity production. Then he contacted Ed Byrnes, a Shadyside resident and third-generation owner of bakery supplier Byrnes & Kiefer, to make both the precise cookie dough mix and icing in bulk.

That marked the beginning of Eat’n Park’s efforts to establish a bakery in each restaurant, and today customers pick up Smiley cookies and other beloved favorites like honey buns, brown bread, and grilled stickies.

Smiley is now celebrating 25 years, over which time Eat’n Park has sold or given away 100 million of the trademarked cookies and come to be known as “the place for smiles.” Twelve million cookies are produced annually. For the last Super Bowl alone, orders were filled for 600,000 cookies trimmed in black and gold icing. Custom-designed cookies are now available online at www.smileycookie.com for shipment anywhere in the country. And now there is a new mini-Smiley cookie, with fewer than 100 calories.

The smaller cookie is one component of LifeSmiles, an initiative developed by an employee team championed by Broadhurst’s wife, Suzy, who recently retired after 17 years as director of corporate giving. In 2010, the company pledged to contribute $1 million and 20,000 volunteer hours over the next five years toward promoting healthier eating

and more physical activity for kids and their families.

Suzy Broadhurst realizes people are still going to order French fries, but she prefers there be an alternative. “We thought some families may not want their kids to have a great big cookie, so we came up with the mini- Smiley,” she says. “And now you have a choice of receiving a big Smiley cookie, a mini- Smiley, or an apple at the end of your meal.”

Following some very profitable years in the 1990s, the timing was right for the company to diversify to continue to meet its goal of 10 to 20 percent growth in annual sales and earnings. In 1996, Eat’n Park made its initial investment in CURA Hospitality, which provides more than 50 accounts with foodservice for patients in hospitals and residents in senior living communities. Eat’n Park Hospitality Group purchased CURA outright in 1999.There has been further growth since all three of Broadhurst’s sons have joined the family business.

When his father called him in 1996, Jeff Broadhurst was happily working in Chicago at Federated Investors. But the offer to head up sales for a new venture called Parkhurst Dining was too compelling to pass up. He says the transition from selling mutual funds to selling foodservice seemed natural to him. Now with 47 accounts, Parkhurst provides contract dining services for institutions such as Chatham University and Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, as well as corporations like PNC Bank and Google.

Since 2008, Jeff Broadhurst has been CEO of Eat’n Park Hospitality Group, which encompasses the company’s three integrated business divisions. The 42-year-old Shadyside resident says Eat’n Park is a very different place from when he worked part-time as a grill cook during his high school years. “Since the time I really knew it, Eat’n Park has evolved through my dad’s intuition,” he says.

That evolution brought the youngest Broadhurst brother back to Pittsburgh in 2003. As the director of concept development, Mark Broadhurst, 36, of Shadyside, used his experience as director of operations at Kahunaville, a Delaware-based restaurant chain, to launch two Pittsburgh restaurants that are a departure from the traditional Eat’n Park model. In 2006 came SixPenn Kitchen, an upscale eatery in Downtown’s Cultural District that remains a pre-show favorite among theatergoers. More recently, in partnership with the Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy, he led the team that developed The Porch, a new neighborhood bistro located at Schenley Plaza in Oakland.

“Eat’n Park restaurants have a lot of character,” he says. “But I enjoy places with a little more cutting-edge food and a higher energy that comes with the alcohol and beverage side of the business.”

Brooks Broadhurst, 40, of Mt. Lebanon, was actually the first brother to return home to work for the company. He came 16 years ago, after working for Great American Restaurants in Washington, D.C. In his role as senior vice president of food and beverage, he oversees distribution, energy purchase, menu development, online business, and food and beverage procurement, including FarmSource—the company’s initiative to buy from local farms.

With a few taps on his calculator, he estimates that each year the corporation purchases 13 million eggs, 20 million slices of bacon, 2 million pounds of beef, and the ingredients to bake nearly 100,000 strawberry pies.

Once upon a time, sales of $600 meant a good day for one of the Eat’n Park drive-ins. Today, total annual sales—including the 75 Eat’n Park restaurants and all of the Parkhurst and CURA accounts—are in the hundreds of millions. To think that the company serves 50 million meals each year is somewhat mindboggling, concedes Jim Broadhurst.

For more than 25 years, many of those meals have been served up at the Squirrel Hill Eat’n Park by Susie Cookson, whose four children have worked there, too. “I’ve been here longer than the Smiley cookie,” laughs Cookson, until recently a Squirrel Hill resident. And she cares about her regulars. “We always tell our older guests to let us know when they are going away so we won’t worry about them,” she explains.

“We are like family,” says Theresa Heinold, a 24-year veteran server and service supervisor, who works the daylight shift with Cookson. There are closer locations to her home in Crafton, but she doesn’t mind the commute, which involves catching two buses each way. “I’m just very comfortable here,” Heinold says. “This is my second home. I would never go anyplace else.”

It’s a common refrain among the 9,000 employees of Eat’n Park, as well as the restaurant’s dedicated patrons. Just ask Joan Humphrey.

“When my children ask where I want to go for my birthday, I always say ‘Eat’n Park,’” says Humphrey, 78, of Squirrel Hill, who remembers having a Big Boy at the former Eat’n Park on Washington Boulevard. Now she is a fan of the breakfast buffet.

“Oh my word,” she exclaims. “It’s to die for. It has everything I like—scrambled eggs, bacon, sausage, pancakes, and corned beef hash. And the price is right.” But the ultimate for Humphrey is to have dinner and then enjoy her Smiley cookie during a movie at the Manor Theatre.

Both the Broadhurst family and the company take pleasure in giving more than their fair share. Committed to donating more than five percent of pre-tax corporate profits to charities, their goodwill and philanthropy have been spread far and wide for many years. Hundreds of organizations—including Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC, The Children’s Institute, the Pittsburgh Area Jewish Committee, The Children’s Home of Pittsburgh, the Women’s Center & Shelter of Greater Pittsburgh, as well as numerous other United Way agencies—have been beneficiaries of their generosity.

“We have probably touched everyone in this community at some point or another,” Suzy Broadhurst says.

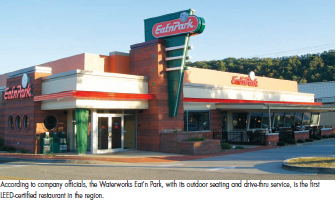

Indeed, the Broadhurst family has as much fun giving as it does innovating. Demonstrating the company’s commitment to conservation and sustainability, the Waterworks Eat’n Park near Fox Chapel is the region’s first restaurant to have LEED gold certification, featuring recycled construction materials and a solar reflective roof. Its wind turbine generates enough electricity to power its exterior and parking lot signage, and, like all Eat’n Park restaurants, it recycles cooking oil for use as biofuel.

From espresso to outdoor seating, living walls to green roofs, the company stays on top of its game. Soon half of the restaurants will have drive-thru service. “I guess we’ve almost come full circle,” says Jim Broadhurst, amused when asked if “drive-thru Eat’n Park” wasn’t an oxymoron.

“The conventional wisdom in the restaurant business is that you can’t be all things to all people,” says Cox, who retired as president in 2006 and still serves on the board. “I think Eat’n Park is a strong argument to the contrary. We’ve thrived on satisfying our customers 24/7, with a full menu, full service, eat-in or take-out, breakfast anytime, buffets and bakeries, steak and liver, pot roast and cod—even poached eggs, which almost no other restaurant will prepare. Jim never wanted to cut back. Only add on and move forward and do whatever it takes to make the customer happy.”

So what’s next?

“We have been working on a spin-off of Eat’n Park that will be geared toward going into higher density, urban locations,” Mark Broadhurst says. “We want to take what people really love about Eat’n Park restaurants and put that into a new package that will be a little louder, have a little more energy, and be something that can go into Oakland, South Side, Shadyside, where we have never been

able to put in a real traditional 7,000 squarefoot Eat’n Park.”

One thing is certain. Whatever Eat’n Park decides to do next, we’ll be waiting— and smiling.

Special thanks to Bob Moore, former president of Eat’n Park, for his unpublished history “Welcome to Eat’n Park, the Early Days,” and to Brian Butko, author of “Klondikes, Chipped Ham & Skyscraper Cones.”

With many thanks to SHADY AVE magazine for granting me permission to reprint on my website.